In ELTWeekly (8 Sep 2020), I mentioned two uses of the present simple and present progressive, to talk about the future. Here are the two examples I used:

- Plan: “I am taking my holiday in Ibiza this year.” Pres. progressive.

- Unalterable plan: “The train leaves Paddington at 17.42.” Pres. simple

I’ve already talked about going to and will, and now I want to continue my exploration of the future, that unknown country, by looking at how we use these two tenses.

The first one is the Plan. Here are two examples:

Hurry up, I’m leaving soon.

Hurry up, the bus is leaving soon,

The first sentence is my plan, and I don’t want to change it. The second one is also a plan, and can’t be changed by the speaker, who is a passenger, could perhaps be changed by the driver, and could certainly be changed by the manager of the bus company. So in both cases, changing the departure time is an issue, but perhaps not impossible to do. The events are what you could call “semi-fixed”

The second one, the Unalterable Plan. Here’s an example:

“Our bus leaves at 7.45.”

This is a plan, and – like the previous sentence – it could probably be changed by the company with some difficulty, but it feels more fixed, more unalterable, than the previous sentence. The difference between these two is in the speaker’s mind.

Here’s a story about what happened to me when I was the boss of a chain of schools:

I wanted one of my school directors, Alan, to do a job for me, and also knew he was going on holiday, so I said:

- When are you leaving?

- I leave at 6.15 a.m. on Monday.

Without thinking about it, I wanted to suggest that it was in his power to change the time of departure, so I said “. . . are you leaving”, not “. . . do you leave?” He could have replied “I’m leaving” or even “I’m going to leave”, but that would have suggested that he could change the beginning of his holiday and do what I wanted first, but he didn’t want to, so he chose the verb form to make the event seem unalterable. It worked, mostly because I didn’t want a confrontation, but also because I had other ways of solving my problem, so I said:

- Okay Alan, enjoy it.

And Alan went on holiday, on Monday (at 6.15 a.m. I imagine).

Here is a shot from a video I made about the present simple. It talks about all the uses, including plans:

And here’s the video.

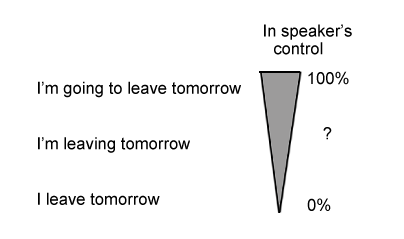

Nothing in the future is unalterable (except, as the Chinese say, death and taxes); these examples are about feelings and attitudes. If you want to make it sound unalterable, use a present simple, “leaves”. If you are willing to accept the idea that it might be changed, although not easily, use a present progressive, “is leaving”. And if you are willing to take total responsibility, say “going to leave”.

Here is a way of looking at three forms:

Of course, “It’s more complicated than that . . .”, but isn’t everything?

Note on the “more complicated” stuff

1 I think the most interesting fact about the future in English is that we don’t have a future tense, which shows that the language recognises an important fact: we can’t exchange information about future events in the same way that we can with past and present events.

We cannot know what will happen in the future, but we can have intentions, we can make predictions, and we can have plans.

2 I said above: “The difference between these two is in the speaker’s mind.” When we use language, we need to think about what the speaker wants to convey. First there is the idea. But are they speaking calmly? With emotion? Anxious to persuade us? Simply stating a fact? Listen carefully: can you tell from the voice, the body language, the emphasis, what the speaker really means, and what he is really trying to achieve with his words? It’s not easy, but it is fascinating to try!